by Tim Malim, former Manager of the Cambridgeshire County Council Archaeological Field Unit.

The massive earthwork monument known as Fleam Dyke consists of a 7-8m high bank and ditched barrier which ran for 5km from Balsham to Fulbourn. Possible extensions to it occur at both the south and north ends, and a further part of it might exist from Quy Fen to the River Cam at Fen Ditton. The main part of Fleam survives today as a footpath and parish boundary, but historically the northern part was also the boundary between Flendish and Staine Hundreds. The Moot for these Hundreds was at Mutlow Hill, a Bronze Age barrow which had clearly been an important landmark for many centuries before its use as an Anglo-Saxon meeting place. Apart from the 4,000 year old cremated burials for which it was originally built, rare third century BC Greek coins have been found close to the burial mound. It was reused in Roman times for a temple, and it is no accident that Fleam Dyke passes right beside it. Mutlow rests on the top of a hill, and overlooks the junction of several routeways (including the Icknield Way) where they meet and cross Fleam Dyke.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, human remains and Anglo-Saxon weapons were reported as having come from Fleam Dyke and its name may derive from the Old English for “flight” or “fugitive”. Proper investigations were undertaken by Cyril Fox and William Palmer, whose excavations and research in 1921-2 established three important points: that the construction was post-Roman, that no causeway had been left for access along the Icknield Way, and that an Anglo-Saxon estate charter of 974 mentions the Dyke as part of its boundary. The interpretation favoured by many during the later part of the last century was that the Fleam Dyke was built to defend the East Anglian kingdom in its wars with Mercia during the seventh century.

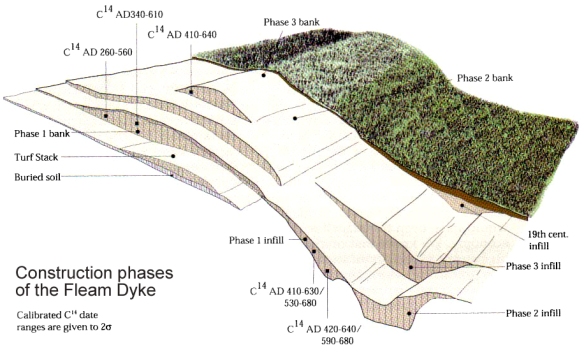

The widening of the A11 in 1991 gave the opportunity for further excavation using modern methods of investigation and scientific techniques to help with analysis. The results demonstrated that Fleam Dyke was a complex monument with no single period of construction, but instead at least three distinct building phases and a number of lesser episodes such as layers of turf-growth representing periods of stabilisation. Beneath the core of the bank, a buried soil survived with the shells of contemporary snails, which showed that Fleam Dyke had been built into an open landscape of gazed grassland and disturbed ground. A fourth century Roman coin was also found beneath the bank, but of more importance for dating purposes was retrieval of animal bone from key deposits so that a sequence of radiocarbon dates could be established. By mathematical modelling it has been possible to refine the range of dates which each individual sample spanned, so that we can say that the first phase of Fleam was built between 330- 510 AD and that the last phase of bank construction occurred between 450 – 620 AD.

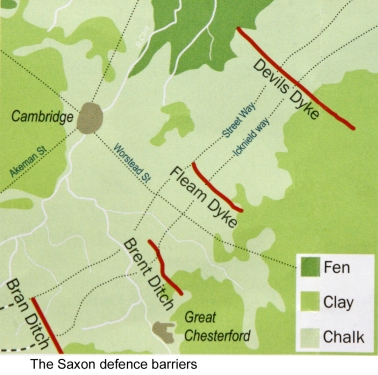

Fleam Dyke is the most complex of a group of similar linear earthworks that ran from the wooded hills in the south to the wet areas of springs, rivers and fens in the north, effectively cutting off access to East Anglia along the Icknield way zone. Based on the dating evidence from Fleam it would seem these barriers were built by Anglo-Saxon immigrants to defend their core settlements in eastern Cambridgeshire, Norfolk and Suffolk against Romano-British counter attacks in the 5th century AD. Their ultimate line of defence was the Devil’s Dyke, from Wood Ditton to Reach, built in a single episode and stretching for 11 kms. To the west of Fleam, two dykes, Bran and Brent, are also known; but it is only Fleam that seems to have so many phases in its construction. This could be because it was built, taken, then retaken and refortified a number of times during the fluctuating fortunes of war during the Dark Ages.

Finally, these Anglo-Saxon dykes are very large monuments, and it is probable that their construction has destroyed evidence for earlier, prehistoric boundaries running along the same line. The location of Fleam Dyke, running as it does through a Bronze Age barrow and Roman temple, to Shardelowes Well at Fulbourn (springs were often sacred sites and the focus for ritual activity), and possibly beyond to meet with the Wilbraham River at a Neolithic causewayed camp, strongly suggests a close association with the past. Such a relationship with sacred sites perhaps imbued the Dyke with a symbolic meaning which it is now difficult for us to comprehend, but which may have helped to give an added dimension to the more pragmatic defensive function of this boundary.

Reference: Malim T et al 1997 ‘New Evidence on the Cambridgeshire Dykes and Worsted Street Roman Road’. Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society Vol. 85, pp. 27 – 122.